Originally posted on 11 Nov 2009

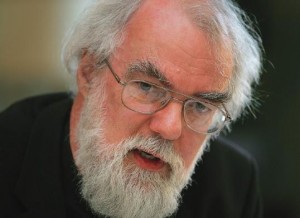

Recently, Dr Rowan Williams gave an excellent speech on the issue of our responsibility towards Creation and a Christian response to environmental crises. The Bible has a clear message about caring for the environment – not just for the here and now, but also because at the end of time this planet will be renewed and restored to pre-Fall glory and be the paradise heaven of God’s Kingdom.

Recently, Dr Rowan Williams gave an excellent speech on the issue of our responsibility towards Creation and a Christian response to environmental crises. The Bible has a clear message about caring for the environment – not just for the here and now, but also because at the end of time this planet will be renewed and restored to pre-Fall glory and be the paradise heaven of God’s Kingdom.

I don’t agree with everything Dr Williams says, but his message is well made and worth listening to. You can read it on his own website, listen to it online (42Mb MP3), or see an extract below.

Act local as well as national urges Archbishop

Tuesday 13 October 2009

In a lecture today at Southwark Cathedral (sponsored by the Christian environmental group Operation Noah) Dr Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, sets out a Christian vision of how people can respond to the looming environmental crisis.

“The Climate Crisis: Fashioning a Christian Response.”

Introduction

As a matter of fact, I don’t want to talk about climate crisis as the first thing on the agenda, despite tonight’s title. I think that we’re only going to be able to shape a robust and creative Christian response to this or any other of our current crises if we step back a bit and try to understand why so much of what’s wrong has its roots in a shared cultural and spiritual crisis. The nature of that crisis could be summed up rather dramatically by saying that it’s a loss of a sense of what life is. I don’t mean ‘the meaning of life’ in the normal way we use that phrase. I mean a sense of life as a web of interactions, mutual givings and receivings, that make up the world we inhabit. Seeing this more clearly helps us dismantle the strange fictions we create about ourselves as human beings. We are disconnected and we need to be reintroduced to life.

So I’m going to outline some of the ways in which the Jewish and Christian traditions offer a way into this – not least through the remarkable story of Noah. I’m going to try and show how the biblical picture presents us with a humanity that can never be itself without taking on the care and protection of the life of which it’s a part. And I want also to make some links to other aspects of our present situation that intensify the feeling of crisis, and to suggest how our responses to the climate crisis and other ecological challenges naturally feeds in to our responses to the wider economic and social malaise as well. I’ll have something to say about the practical steps we can all take in response to these things; but at the heart is the challenge to live with different images in our minds. The story of Noah is a great archetypal story, one to which we constantly return to learn something of the truth of our own situation and make better sense of it. So let’s start with some of the familiar images from that story.

1.

If there’s one thing most people still remember about Noah and the flood, it’s that the ark was full of animals. Thanks to a variety of popular songs – including the children’s cantata, Captain Noah and his Floating Zoo, which we have probably all heard at primary school concerts – some of us many times –– and plenty of picture books and cartoons, you’re likely to think of Noah as surrounded by the animals who came in two by two. Forgetting for a moment the complications of the biblical text, with its distinction between the seven pairs of ritually clean animals and the single pair of unclean animals required, the story is clearly about how the saving of the human future is inseparable from securing a future for all living things. It’s not just that Noah collects specimens of animal life; he collects breeding pairs, and, when the floodwaters have subsided, they are famously told to go and ‘multiply’ (Gen.8.17). Noah is made responsible for the continuation of what we would call an ecosystem. In all sorts of ways, the story in Genesis deliberately echoes the story of creation itself, using many of the same words and phrases. The creation stories of Genesis 1 and 2 see the creation of humanity as quite specifically the creation of an agent, a person, who can care for and protect the animal world, reflecting the care of God himself who enjoys the goodness of what he has made. With Noah that care is expressed in terms of saving a future in which humanity and the animal world share the same space.

In the words of the theologian Michael Northcott , ‘In contrast to the prideful destruction visited on the earth by his violent neighbours, Noah submits patiently to the humble demands of caring for the many animals he intends to save from destruction’ (A Moral Climate. The Ethics of Global Warming, p.73). The image of Noah summoning the creatures to the ark may also be meant to recall God bringing the animals to Adam so that they can be named (Gen.2.19): once on the scene, humanity has to establish its relationship with the animal world, a relationship in which meaning is given to the whole world of living things through the human reflection of God’s sustaining care.

I shan’t labour the point that reading Genesis as if it licensed the exploitation of the rest of creation is a major mistake. Nothing could be clearer in the biblical text than the belief that humanity is meaningless seen independently of the world of diverse life-forms in which it is embedded. The flood story ends with the making of a covenant, a binding treaty, not just between God and humanity but between God and all living things (Gen.9. 8-17): God is committed to life, to the continuance of life on earth, and whatever happens he will not let life disappear. And although the focus in the story of the flood has been on animal life, it is clear that the horizon of the text extends much wider. The one thing we should not imagine is that God’s covenant means that we have a blank cheque where the created world is concerned. The text points up that God’s promise has immediate and specific implications about how we behave towards all living beings, human and non-human. It is not a recipe for complacency or passivity.

Read in this way, the Bible seems to be saying that creation finds its focus in three things: the possibility of life, the transmission of life and the interrelated diversity of life. So if we focus, as we can hardly help doing, on humanity as the supreme creative possibility – the form of life that reflects the love and intelligence of the creator – this has important implications. The supreme possibility is to show something of the nature of God within the creation, and the ‘specialness’ of humanity turns out to lie in its role as protecting (through the exercise of that love and intelligence) life overall, not only of human life; it is a crucial part, but still only a part, of the interdependence of all living things. So for humanity to be a point of focus in creation is not for it to be separate from the rest of creation or to have solitary privileges and powers over creation. It is to realise that it is unimaginable without all those other life-forms which make it possible and which it in turn serves and conserves. And if that is the case, then respect for humanity, a proper ethical account of humanity, has to be bound up with respect for life itself in all its diversity.

One of the greatest Christian thinkers of the twentieth century, Karl Barth, when he discusses the foundation of ethics (Church Dogmatics III.4 # 55.1), makes very creative use of the idea of respect for life as a basic category. Life, he notes, is something that cannot be owned, only lived (p.329). It is something developing through time; something experienced as gift not possession, something made real by relationship with the creator. He goes on to express his reservations about trying to connect the way this works out ethically in human affairs with any ideas about non-human life in general. But the Noah story suggests that these reservations are misplaced. Genesis tells us that when we are called to relationship with our creator, we are in the same moment summoned to responsibility for the non-human world. That’s how we express and activate our relationship with the creator, our reality as made in God’s image. In this way, the creator has joined together the sacredness of human life with that of life itself. There is no way in which we can grasp human dignity and value it independently of human life’s involvement with all other life, vegetable and animal – the variegated life of the rain forest as well as the multiple species of pollinating bees.

This vision of an ethical perspective based on reverence for the whole of life is not often heard in discussions among Christians about environmental ethics but perhaps it deserves some further exploration. The Noah story – and the Jewish and Christian ethical insights that can be built upon it – lays out a clear vision, a very specific definition of the human vocation as including the care and preservation of the conditions of all life, care for the future of life. God may promise in the aftermath to the story of the flood that life will not be wholly destroyed, but that does not lift from us the burden of responsibility for what confronts us here and now as a serious crisis and challenge. To act so as to protect the future of the non-human world is both to accept a God-given responsibility and appropriately to honour the special dignity given to humanity itself. In Christian theological terms, it is to accept the renewed human dignity and authority that flows from the self-giving of Christ and his bodily resurrection, which is itself a sign of God’s concern with the material world and his commitment to its transfiguration. Thus respect for the living material world and human self-respect belong together. The restoration or salvation of one is bound up with the other.

2.

How then do we live as humans in a way that honours rather than endangers the life of our planet? Or, to put it slightly differently, ‘How do we live in a way that shows an understanding that we genuinely live in a shared world, not one that simply belongs to us?’ This would be a good question even if we were not faced with the threats associated with global warming, with the reduction of biodiversity, with desertification and deforestation, with fuel and food shortages. We should be asking the question whether or not it happens to be urgent, just because it is a question about how we live humanly, how we live in such a way as to show that we understand and respect that we are only one species within creation. The nature of our crisis is such that we can easily fall back on a position that says it isn’t worth trying to change our patterns of behaviour, notably our patterns of consumption, because it’s already too late to arrest the pace of global warming. But the question of exactly how late it is isn’t the only one, and concentrating only on this can blind us to a more basic point. If we are locked into a way of life that does not honour who and what we are because it does not honour life itself and our calling to nourish it, we are not even going to know where to start in addressing the environmental challenge.

Alastair McIntosh in his splendid book, Hell and High Water. Climate Change, Hope and the Human Condition, speaks of what he calls our current ‘ecocidal’ patterns of consumption as addictive and self-destructive. Living like this is living at a less than properly human level: McIntosh suggests we may need therapy, what he describes as a ‘cultural psychotherapy’ (chapter 9) to liberate us. That liberation may or may not be enough to avert disaster. We simply don’t know, though it would be a very foolish person who took that to mean that it might be all right after all. What we do know – or should know – is that we are living inhumanly.

Start from here and the significance of small changes is obvious. If I ask what’s the point of my undertaking a modest amount of recycling my rubbish or scaling down my air travel, the answer is not that this will unquestionably save the world within six months, but in the first place that it’s a step towards liberation from a cycle of behaviour that is keeping me, indeed most of us, in a dangerous state – dangerous, that is, to our human dignity and self-respect. McIntosh writes that ‘unless the psycho-spiritual roots of this are grasped, our best efforts will amount to no more than “displacement activity”‘ (p.219). So we must begin by recognising that our ecological crisis is part of a crisis of what we understand by our humanity; it is part of a general process of losing our ‘feel’ for what is appropriately human, a loss that has been going on for some centuries and which some cultures and economies have been energetically exporting to the whole world. It is a loss that manifests itself in a variety of ways. It has to do with the erosion of rhythms in work and leisure, so that the old pattern of working days interrupted by a day of rest has been dangerously undermined; a loss of patience with the passing of time so that speed of communication has become a good in itself; a loss of patience which shows itself in the lack of respect and attention for the very old and the very young, and a fear in many quarters of the ageing process – a loss of the ability to accept that living as a material body in a material world is a risky thing. It is a loss whose results have become monumentally apparent in the financial crisis of the last twelve months. We have slowly begun to suspect that we have allowed ourselves to become addicted to fantasies about prosperity and growth, dreams of wealth without risk and profit without cost. A good deal of the talk and activity around the financial collapse has the marks of McIntosh’s ‘displacement activity’ – precisely because it fails to see where the roots of the problem lie; in our amnesia about the human calling.

So some of our habits in the wealthy world have the effect of separating us from our humanity by separating us from the very processes of life itself, from the experience of time and growing, and of death itself as something inevitable. We have seen growing evidence in recent years of a lack of correlation between economic prosperity and a sense of well-being, and evidence to suggest that inequality in society is one of the more reliable predictors of a lack of well-being. It looks very much as if what we need is to be reconnected rather urgently with the processes of our world. We shouldn’t need an environmental crisis to establish that the developed world has become perilously out of touch with the experience of those living in the least developed parts of the world and with their profound vulnerabilities and insecurities. But it is the case that this crisis has focused as few other things could the real cost of illusion, the cost of the progression traced by Alastair McIntosh, perhaps too dramatically for some tastes, from pride to violence to ‘ecocide’ (see esp. McIntosh, op.cit., chapter 5). And this means that we have to ask whether our duty of care for life is compatible with assuming without question that the desirable future for every economy, even the most currently successful and expansionist, is unchecked growth. If the effect of unchecked growth is to isolate us more and more from life – from the complex interrelations that make us what we are as part of the whole web of existence on the planet – then we cannot continue to grow indefinitely in economic terms without moving towards the death of what is most distinctively human, the death of the habits that make sense in a shared world where life has to be sustained by co-operation not only between humans but between humans and their material world.

Just to be clear: we must not romanticise poverty and privation and we cannot deny that economic growth may be a powerful driver of human liberation. Humanity is undermined just as surely by material wretchedness and privation and the constant struggle for subsistence, and it is right to work for a world in which there is security of work and food and medical care for all, and to try and create local economies that make local societies prosper through trade and innovation. But the question more and more people are asking is whether there are macro-economic models that would allow us to see investment in public infrastructures and the development of sustainable technologies as priorities for a healthy economy, rather than a simple growth in consumer power. The recent report, Prosperity Without Growth, from the Sustainable Development Commission, outlines what sort of areas would need to be rethought if we took such an approach and tried to balance the need for a stable and productive economy with the need for investment directed towards ‘resource productivity, renewable energy, clean technology, green business, climate adaptation and ecosystem maintenance and protection’ (p.82). It would mean revising a lot of assumptions about the timescale and character of profit and about the balance of private and public good. But without some such rethinking of our current obsession with growth in consumerist terms, we can be sure of two things: inequality will not be addressed (and so the powerlessness of the majority of the world’s population will remain as it is at the moment); and the dehumanising effects of the culture of consumer growth will worsen. Only if we start thinking along these lines can we see our way through the difficulties often referred to about holding together the imperative of environmental care and the imperative of economic development.

Mike Hulme, in a provocative and original new book, Why We Disagree About Climate Change, argues that the anxieties around global warming and related matters are actually a welcome opportunity for us to look hard at fundamental issues concerning our social and ethical situation. He quotes (p.354) the somewhat startling remarks of a former Canadian government minister who said that even if the science around climate change was mistaken, the focus on the question had provided the best possible impetus towards more equality and justice in the world. Put like this, the remark is a bit of a hostage to fortune. I’m not sure it would be helpful to make moral capital out of erroneous science, and it is certainly not helpful to give a handle to those eager to encourage scepticism about the science of climate change. But presumably the point is to move us away from seeing the question only in terms of a problem-solving exercise. Hulme suggests that to come at the set of issues around climate change in terms of an agenda to do with fundamental justice has energising and mobilising power – more so than an approach based simply on the fear of catastrophe, which can have a paralysing effect. We need to think about this as a call to do what is in its own right good and life-giving for us – a call to be more human.

Mike Hulme’s book is helpful as a warning against too readily buying in to extravagant language about ‘solving’ the problem of climate change as if it were a case of bringing an uncontrolled situation back under rational management, which is a pretty worrying model that leaves us stuck in the worst kind of fantasy about humanity’s relation to the rest of the world. Instead, he recommends a deliberately many-faceted approach, recognising that there is no one ecological problem waiting for a solution and that the various levels of challenge need as wide a variety of creative response as we can muster. I shall be coming back in a moment to look at some of the specifics this involves.

3.

To summarise so far: living in a way that honours rather than threatens the planet is living out what it means to be made in the image of God. We do justice to what we are as human beings when we seek to do justice to the diversity of life around us; we become what we are supposed to be when we assume our responsibility for life continuing on earth. And that call to do justice brings with it the call to re-examine what we mean by growth and wealth. Instead of a desperate search to find the one great idea that will save us from ecological disaster, we are being invited to a transformation of individual and social goals that will bring us closer to the reality of interdependent life in a variegated world – whether or not we find we can ‘save the planet’.

Hulme is right surely that the scale and complexity of the challenge we face mean that no one solution will suffice. We need to keep up pressure on national governments; there are questions only they can answer about the investment of national resources, the policy priorities underlying trade, transport and industry and the legal framework for controlling dangerous and destructive practices. But we ought to beware of expecting government to succeed in controlling a naturally unpredictable set of variables in the environment or to produce by regulation a new set of human habits. We need equally, perhaps even more, to keep up pressure on ourselves and to learn how to work better as civic agents. Hulme gives the example of the Carbon Reduction Action Groups, first established in 2006, as a means of expressing local civic responsibility by working with the idea of personal carbon allowances and sharing ‘skills in lower-carbon living’. To quote: ‘CRAGS adopt the position that individuals need not accept the existing political and governance arrangements and can subvert these traditional arrangements through local action’ (307). And in addition to all this, encouraging local government initiatives and legal challenges to bad business practice are just as necessary a part of a comprehensive strategy; pressure in this area needs to be as effective as campaigning directed towards national governments. A campaigning strategy targeted exclusively at the level of national directives or international protocols ignores the potential of a broad platform of tactics in diverse contexts. More importantly it ignores the potential of the crisis to awaken a new confidence in local and civic democracy, its potential to foster a new sense of what is politically possible for people who thought they were powerless.

The threat posed by climate change and environmental degradation tends to make us think about survival and look for solutions that will guarantee survival. That’s a reasonable response to any threat; but the sheer complexity of this situation and the continuing uncertainty about some of the precise detail (how late is it? have we reached the ‘tipping point?) make us especially vulnerable. We are bound to realise sooner or later that easy solutions are not at hand and that there is no one cause of the whole crisis that will allow us to point to some single scapegoat. This in turn makes us vulnerable to panic on one hand, apathy on the other, and the illusion that someone will both take the blame and assume the responsibility of finding a solution – usually meaning a series of grand technological solutions requiring massive investments of money nobody seems to have.

What if we reframe the question more like this? ‘When we find ourselves facing massive insecurity of this sort and when we sense that we have somehow sacrificed our happiness along the way, what is it that we have lost? And how can we work to restore it?’ That kind of question can be answered effectively only if we have a robust picture of what human capacity and responsibility should look like. And this surely is the main contribution to the environmental debate that religious commitment can make. With due respect to one recent secular commentator, the role of religion here is not to provide an ultimate authority that can threaten and coerce us into better behaviour; it is to hold up a vision of human life lived constructively, peacefully, joyfully, in optimal relation with creation and creator, so as to point up the tragedy of the shrunken and harried humanity we have shaped for ourselves by our obsession with growth and consumption. In the words of Michael Northcott, ‘industrial humans increasingly experience their identity in terms of the things that they have acquired, instead of in their being creatures’ (op. cit., p.186); and we might recall the words of Karl Barth quoted earlier about life as something to be lived, not owned.

So, without trivialising or minimising the ravages that have been inflicted on the whole material environment by the consequences of industrialisation, we could say that the human soul is one of the foremost casualties of environmental degradation, in the sense that the processes of environmental damage have both reflected and intensified a basic spiritual malaise. Many of the things which have moved us towards ecological disaster have been distortions in our sense of who and what we are, and their overall effect has been to isolate us more and more from the reality we’re part of. Our response to the crisis needs to be, in the most basic sense, a reality check, a re-acquaintance with the facts of our interdependence within the material world and a rediscovery of our responsibility for it. And this is why the apparently small-scale action that changes personal habits and local possibilities is so crucial. When we believe in transformation at the local and personal level, we are laying the surest foundations for change at the national and international level. They are not two alternative paths but aspects of one essential impulse, the restoration of a healthy relation with our world.

So whatever we do to combat the nightmare possibilities of wholesale environmental catastrophe has to be grounded not primarily in the scramble for survival but in the hope of human happiness. The opportunity presented to us is an opportunity of pressing for a deeper and more searching public debate about the character of such happiness, the character of the human good. It is encouraging that an increasing number of social philosophers are moving the discussion in this direction. Michael Sandel’s work, Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do, for example, concludes that we have succumbed to thinking about justice essentially in connection with individual rights rather than in the context of asking what actions are in themselves good; and the result, he says, has been an abstract and legalistic notion of rights and a very ‘thin’ idea of justice itself. If we are to move on from this, he continues, we are bound to accept a greater degree of real argument in our public life about the nature of the good life – which means allowing moral and religious convictions to be far more visible in the public sphere. ‘A politics emptied of substantive moral engagement makes for an impoverished civic life’ (p.243). What is true for our discussion of civil and criminal justice holds equally for our understanding of the moral dimension of the environmental crisis we face – including the issue of environmental justice itself.

4.

We seem to have travelled some way from Mount Ararat. But the crucial thread running through these diverse considerations is the question of what we mean by life and how we honour it appropriately in our practice, individual and social. To be human, in the biblical world view, is to be given a responsibility for the future of life. We become less than human when we stifle possibilities for life, when we ignore the need for balanced diversity – or forget the degree of our ignorance about its detailed workings. Creation, the total environment, is a system oriented towards life – and, ultimately, towards intelligent and loving life, because in the Creator there is no gap between life, intelligence and love. The biblical vision does not present us with a humanity isolated from the processes of life overall in the cosmos, a humanity whose existence is of a different moral and symbolic order from everything else; On the contrary the unique differentiating thing about humanity is the gift to human beings of conscious, intelligent responsibility for the life they share with the wider processes of the world. Because this life reflects in varying degrees the eternal life of God, we have to say, as believers, that the possibility of life is never exhausted within creation: there is always a future. But in this particular context, this specific planet, that future depends in significant ways on our co-operative, imaginative labour, on the actions of each of us. Just as importantly, our human dignity itself is bound up with these actions. What we face today is nothing less than a choice about how genuinely human we want to be; and the role of religious faith in meeting this is first and foremost in setting out a compelling picture of what humanity reconciled with both creator and creation might look like.

Conclusion

How does this choice become specific? All I want to do by way of conclusion is to remind you of some of the points already touched upon. First, we all have in our minds at the moment the forthcoming Copenhagen summit, and we are all aware of the imperative to urge leaders at the most senior level to attend and to create a suitably serious plan for taking forward within a tight time frame protocols about carbon reductions – carbon taxes, investment in new energy-efficient technologies (using the gains from carbon taxes among other things), the international acceptance of accounting regimes that factor in environmental cost. In recent weeks, we have had unexpected signs that the East Asian countries are readier than we might have imagined to put pressure on the economies of the US and Europe. The idea that fast-developing economies are totally wedded to environmental indifference because of the urgency of bringing their populations out of poverty no longer seems quite so obvious a truth; and the realisation that unchecked environmental degradation means more poverty for everyone in the (not very) long run is clearly taking root.

Then there are the community options. I mentioned the CRAG initiatives earlier, and that is just one example of the effectiveness of collaborative local action. In the same general territory, each of us can bring pressure to bear on institutions we are connected with to conduct a rigorous carbon audit; for those involved in the Church of England, the website of the Shrinking the Footprint initiative offers help with such projects, detailed suggestions for both study and action.

And last, and anything but least, there is what each of us can do to reconnect with reality, as I put it earlier. There are the various specific choices we can make about our refuse, our travel, our domestic energy use – all fairly familiar by now; and once again there are resources available for more detailed proposals. But I’d want also to underline the need for us to change our habits enough to make us more aware of the diversity of life around us. I once suggested that one necessary contribution to a better awareness of these issues was to make sure we went out of doors in the wet from time to time (a suitable lesson from Noah…), and – if we haven’t got gardens of our own – make sure we took opportunities of watching the changing of the seasons on the earth’s surface. This may seem trivial compared with the high drama of ‘saving the world’; but if this analysis is correct, our underlying problem is being ‘dissociated’, and we ought to be asking constantly how we restore a sense of association with the material place and time and climate we inhabit and are part of.

The Christian story lays out a model of reconnection with an alienated world: it tells us of a material human life inhabited by God and raised transfigured from death; of a sharing of material food which makes us sharers in eternal life; of a community whose life together seeks to express within creation the care of the creator. In the words used by both Moses and St Paul, this is not a message remote from us in heaven or buried under the earth: it is near, on our lips and hearts (Rom.10.6-9, Deut.30.11-14). And, as Moses immediately goes on to say in the Old Testament passage, ‘You know it and can quote it, so now obey it. Today I am giving you a choice between good and evil, between life and death…Choose life’ (Deut.30.14-15, 19).

© Rowan Williams 2009

Source: http://www.archbishopofcanterbury.org/2563

One thought on “The Archbishop of Canterbury on Global Warming”