CONTEXT: A few weeks ago, a young girl at a school in South Africa protested against the rules of her school by wearing a fairly sizeable Afro-style hair style. On the face of it, this doesn’t sound like much. But there are many reasons this became a flashpoint for discussion and debate.

- Firstly, it happened in a South Africa that has just experienced a watershed election, where the balance of power is shifting in the whole of society – we’re trying to work out what it means to be South African, rather than post-apartheid South African.

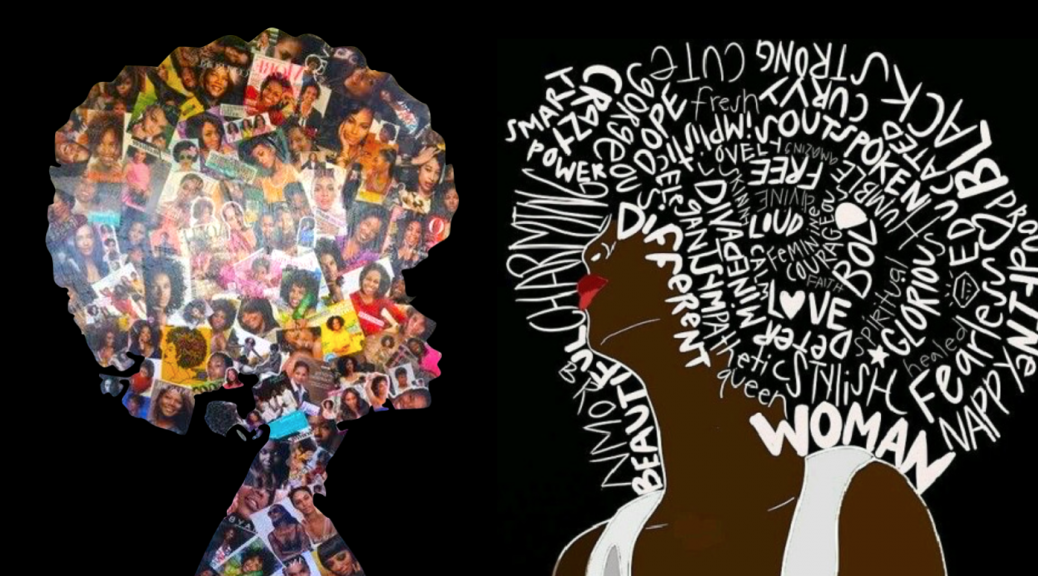

- Secondly, hair is an issue for black women. It just is. I have an adopted black daughter, and hair has been an issue in our home since she arrived. I have spent many hours with her at hair salons, and marvel at what African women must endure to do anything with their hair.

- Thirdly, hair is more than a merely cosmetic issue – it is a political issue. All the way back in the days of slavery, hairstyles distinguished the house slaves (who had to straighten their hair or wear wigs) and field slaves. It was an apartheid test for race – if a pencil stayed in your hair, you were ‘black’. I kid you not – this was happening in South Africa in the 1970s and 80s.

- Fourthly, our world is built with a hidden (but very much intentional and specifically constructive) white heteronormative bias. Most white people (especially white, straight males) do not even notice this. Like fish don’t know they’re swimming in water.

I recently posted a Facebook profile picture with a short statement of support for all the young black women who are standing against their schools’ hair policies. The responses I received to this indicated that many people do not understand the racism inherent in the very system itself. I realised I was one of those people. So, I wrote this:

I am a racist. But I do not want to be one.

I am learning that I don’t even know some of the ways in which I have been raised to be a racist. When I examine my heart, I know I am not a racist. But then my instinct response to an issue is to take the side of the establishment – institutions, systems, structures that are deeply entrenched with Euro-centric bias. I convince myself that this is because I believe in law and order, and that I believe in being civilised and progressive (and I raise only a faint warning alarm in my mind when I tell myself that ‘tradition’ and ‘reputation’ are important, especially in schools). But then I replay the pictures in my mind that illustrate these beliefs of mine. These pictures in my mind are of dark-skinned lawless criminal-types, and light skinned civilised people. Do I actually believe that? No. Of course not. But my mental pictures give me away.

I picture a young Black woman with a big Afro standing next to a young white woman with pink dyed hair and punk tattoos, and I wonder which one would be more distracting in a school classroom. My heart says neither. My head tells me both could be. But the pictures that illustrate these concepts see the dark skinned person as more problematic. I am informed by the news of a young man caught in a criminal act, and I must confess I picture him as black before I wonder if he might be white. It’s a sad default setting brought about by my world and upbringing in South Africa.

I want to say I am not a racist, because these deep pictures are not my lived reality. I treat all people with as much respect as possible. I don’t consciously stereotype or racially profile. In fact, whenever I do anything consciously I am sure that I am definitely not racist. Except when I am. Because much of what we do is not consciously done. We don’t have the mental capacity to take every issue or circumstance back to first principles, in the moment (over time, we definitely do – and we must. This is the hope I have). In the moment, we rely on models and frameworks. And I need to admit that mine are skewed in favour of Eurocentric models – my deep pictures of the world tell me it’s better to be white, and that black culture is inferior. Like a fish that does not know it is swimming in water, my deep mental models often go unnoticed.

Where do these pictures come from? And how can I get rid of them? How is it possible that an enlightened me, with an adopted black daughter and “lots of black friends”, a man who is not scared to go into townships, who works with and for people of all race groups, who has studied diversity and lectures on it, who desires to see all people as equal, who has actively worked for the advancement of the previously disadvantaged, and believes with all my heart that we are all equal; how is it possible that when I honestly look at the deep mental models that shape my view of the world, I have a mental model that defaults to seeing behaviour I don’t understand in black people as not normal, as problematic and as sub human? I have to be honest and admit this.

I don’t want to think of myself as a racist. But I am. A recovering one. But a racist nonetheless.

Thank goodness and thank God that I am becoming more self aware of it, and am learning to spot the signs of it in myself, and that I have friends who have been gracious enough to walk with me gently, and that I am now learning to construct new filters. I can only hope and pray and believe that these filters eventually become my reality, so that the deep dark pictures eventually disappear completely. I do not want those pictures to define my future. But I know they define my past. And, sadly, my present. No matter how good my heart or intentions may be.