Summary

|

Before we move on to look at the two verses in Leviticus that talk of male same-gender sexual acts, we need to look again at how we deal with the Bible, especially the Old Testament Law. Many of these laws are still in place today, but many are not. We need to know what principles are used to determine which laws apply and which do not. We need to look at three specific issues: consistency, punishments and the New Covenant.

Being Consistent with the Old Testament Law

In his book, “A Year of Living Biblically”, Esquire magazine writer, AJ Jacobs, attempted to follow every law laid out in the Old Testament for a full year. Similarly, Christian author, Rachel Held Evans chronicles her attempts to live out the laws and commands for women in the Bible in “A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband ‘Master'”. Neither succeeded in their quests – often hilariously so – because the lists of laws in the Bible (not forgetting that Jewish and Christian traditions add hundreds more) are literally impossible to follow in their entirety. This should give us a clue as to their nature and purpose.

It is fairly simple to see that some of the laws of the Old Testament have fallen away. The most obvious are the dietary and food laws, and the system of sacrifices and offerings. The reason these no longer apply is because they were pointing to what Jesus would do. They showed us that God was holy and that we were not, and they showed us our need for God. When Jesus came, He became the ultimate expression of these truths. We do not need these laws anymore, and we can safely leave them as a historical record that is no longer binding on us. There are also laws related to Israel as a nation. These too have fallen away, as the New Covenant is no longer for a specific nation-state.

But there are some laws that feel universal and eternal. Like “do not kill” and “do not lie”. These are often referred to as the “moral laws” and it is claimed that we can ignore all other laws, but not these.

In theory this sounds good and reasonable. In reality, it’s not as easy to work out which laws are the laws that are strictly moral, and therefore still applicable, and which were only meant for Israel and for a time. Add to this the fact that “The Law” is usually spoken about in the singular. It was a unit, and meant to be treated as such, as James 2:10, for example, tells us, “For whoever keeps the whole law and yet stumbles at just one point is guilty of breaking all of it.” This is how Jesus referenced it too (e.g. Matthew 22:40) – it is meant to be taken as a whole.

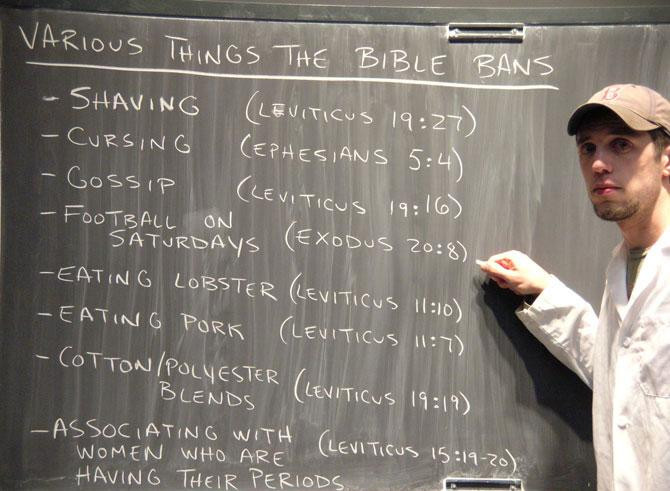

So, how do we as Christians deal with a set of instructions that include prohibitions against things that are considered completely acceptable today? Do we abandon it all? Or embrace it all? Or are there some principles we can use to distinguish which we abandon and which we apply? The biggest issue we have in determining which parts of the Old Testament Law we should apply today is consistency.

The only possible way to do this is by creating categories of laws, claiming that some categories are still in force while others have fallen away or been superseded. This has been the approach of traditional interpreters of the Law. And they claim that the two laws against homosexual behaviour fall into the the “moral” category, which is universal and eternal.

The typical categories traditional interpreters use are:

- Ceremonial or sacrificial – these relate to the Tabernacle and Temple rituals, sacrifices and religious ceremonies. These laws have been fulfilled in Christ’s sacrifice and no longer apply.

- Civic or civil – these relate to political, regulatory and economic rules. These rules were for Israel as a nation, and therefore do not apply to us today.

- Food, dietary, health or cleanliness – these are to do with health and safety laws, and those related to sanitation and diet. These rules were especially for Israel while they were in the desert, and don’t apply to us today. The food laws were specifically put aside by Paul and Peter, and do not apply today.

- Moral – these are rules related to behaviour of people. These are considered universal and eternal, although Jesus and Paul both adapt many of them. It is these rules that some say still apply today. We’ll see below it’s difficult to isolate these from the many laws that no longer apply.

- Cultic – As we’ll see in more detail in the next section of the series, these laws (often called the Holiness Code) relate to idolatry and the religious traditions of surrounding nations. Paul reinterprets these rules, calling them idolatry. The specific rules are not applicable today.

This would be a good model, if only it worked. But it doesn’t. My thesis is simple: these categories are not Biblical, but even if we could come up with a convincing and logically consistent method of allocating laws to each category, I contend that none of these laws are applicable in the New Covenant. Every law we need, and all the moral laws we follow today, come from the New Testament alone.

Categories of The Law

It really is important to note that the Bible does not create these categories. And it is not as simple as some would make out to determine which laws fit into which categories. It’s also important to note that different Biblical scholars would put different laws in different categories, and would even argue about the categories themselves. It really is not as clear as some people would have you believe.

Let me give a few examples to illustrate the problem:

- Exodus 21:16 says: “Anyone who kidnaps someone is to be put to death, whether the victim has been sold or is still in the kidnapper’s possession.” I am sure we all agree that kidnapping is wrong, and that it is a universal, moral law. Does this mean that all the other laws in Exodus 21 are in the same category? Consider verse 7, just before the kidnapping verse: “If a man sells his daughter as a servant, she is not to go free as male servants do.” Is this universal? Are we allowed to sell children into slavery today? If not, then on what basis is one law moral and the other not?

- In Exodus 22:19 we read: “Anyone who has sexual relations with an animal is to be put to death.” Bestiality is certainly a universal, moral law. So, how then do we deal with verse 25, just a few verses later: “If you lend money to one of my people among you who is needy, do not treat it like a business deal; charge no interest.” Is this a universal principle, and how might it apply today? Should Christians be giving interest-free loans? On what basis would we say the one law is eternal, but the other is not? The same applies in Deuteronomy 23:17-23, where prohibitions against prostitution are followed by prohibitions against charging interest.

- Deuteronomy 25:13-16 talks about not using dishonest weights and measures. Is this merely a civil law that has now passed away, or is this a universally applicable moral law about economic justice? It feels like it’s a moral, eternal law about economic justice. What impact does that categorisation have on the previous fascinating command: “If two men are fighting and the wife of one of them comes to rescue her husband from his assailant, and she reaches out and seizes him by his private parts, you shall cut off her hand. Show her no pity.” (Deut. 25:11-12). Is this an eternal law?

- Leviticus 19:28 talks about not having tattoos. What category of law does this belong to? You have to understand the literary and cultural context to know that this is a cultic law. It is not a universal prohibition against tattoos, meant for everyone everywhere. Rather, it is about not joining in with cultic rituals of the surrounding nations.

- When Jesus is asked to summarise The Law, he quotes Leviticus 19:18, saying “love your neighbour as you love yourself.” But the very next verse in Leviticus says, “You shall not breed together two kinds of your cattle; you shall not sow your field with two kinds of seed, nor wear a garment upon you of two kinds of material mixed together.” Are these laws equally universal and moral? What category of laws are these three laws from anyway? We can guess, but can we claim to be sure? I don’t think so.

There are other examples of passages that mix up these “categories”, and of laws that defy simply categorisation, but hopefully these are enough to make the point. It’s not possible to apply any consistent principle to the Old Testament Law that simply and correctly categorises “moral laws”. The reason this is important becomes immediately apparent when you look at the two verses that deal with homosexuality in the Old Testament Law. These verses are Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13. They are part of a section of laws starting at Leviticus 18:1:

“The Lord said to Moses, ‘Speak to the Israelites and say to them: ‘I am the Lord your God. You must not do as they do in Egypt, where you used to live, and you must not do as they do in the land of Canaan, where I am bringing you. Do not follow their practices. You must obey my laws and be careful to follow my decrees. I am the Lord your God.'” (Lev. 18:1-4).

The section ends with a similar statement in Leviticus 20:23-24:

“You must not live according to the customs of the nations I am going to drive out before you. Because they did all these things, I abhorred them. But I said to you, ‘You will possess their land; I will give it to you as an inheritance, a land flowing with milk and honey.’ I am the Lord your God, who has set you apart from the nations.”

It seems clear that what is in these chapters are cultic laws, related to how Israel is to be different to the surrounding nations and prohibiting them from following the practices of the nations they replaced in the Promised Land.

However, the first thirteen laws in Lev. 18 all relate to prohibited familial sexual relations (everyone from your mother-in-law to your daughter). These all seem like fairly universal laws, and not many people would argue with them today. Are these moral laws, then? They could equally be classified as civil laws, health laws (related to genetic in-breeding that we now know about) or cultic laws (which is what the literary context is suggesting). This is the first important principle: just because a law is still applicable today, doesn’t mean that the original author of Leviticus thought of it as a moral, universal and eternal law.

The heading of the section seems very clear: these are cultic laws. We cannot simply list these as moral laws when the Biblical context clearly states they are cultic in nature, and therefore only temporary. Our culture may agree with these laws. Most cultures throughout history may agree with these laws. But it is very clear in the context of Leviticus 18 that they are cultic in nature. On what basis would we categorise them differently? A very strong point made by those who hold a traditional interpretation of the Bible is that we cannot adjust our view of God’s Law based on our feelings, on our culture or on what we think is right and wrong. The only correct basis is the Bible and what it says. I agree. And on that basis, these laws are cultic, and therefore not applicable today.

The next law in this list is Lev 18:19, which prohibits sex with a menstruating woman. And this is a good example of the consistency issue. Is this a moral law, universally applicable? Or is it a cultic law, as the context suggests? If the other laws in this section of the Bible are meant to be eternal and universal, then so must this one be applied today. So we must ask: is it really an abomination to have sex with a woman who is menstruating? Or is it something we can do today, if we want to? You cannot have this both ways: if you believe the laws against homosexuality found in Leviticus apply today, then this prohibition against sex with a menstruating woman must apply too.

After a prohibition against sex with your neighbour, the next law in Lev 18:21 is about child sacrifice. We know that this law is cultic as the specific god Molech is named, and we know from history that child sacrifice was part of the cultic worship of this deity. This law is repeated a few times across Exodus, Deuteronomy and through the prophets.

The next law is the one about two men having sex, followed by a prohibition against bestiality. We’ll look at these in more detail in the next section of this series.

And then, just to be clear, Leviticus reiterates that these are cultic laws: “Do not defile yourselves in any of these ways, because this is how the nations that I am going to drive out before you became defiled.” (Lev. 18:24) “Keep my requirements and do not follow any of the detestable customs that were practiced before you came and do not defile yourselves with them. I am the Lord your God.” (Lev. 18:30). This is repeated again in Leviticus 20:22, showing the connection between these chapters. And then: “You are to be holy to me because I, the Lord, am holy, and I have set you apart from the nations to be my own.” (Lev. 20:26).

We’ll look in more detail at cultic laws in the next section of this series, but for now my point is this: either all cultic laws are applicable today, or none are. But it gets even more difficult to justify these legal categories when you move into Leviticus 19.

In Leviticus 19:3 and 19:30, the Sabbath is mentioned. Which category of laws does observing the Sabbath fall into? It is part of the sacrificial system of worship, and therefore a ceremonial or sacrificial law. It is also part of the civic law, since it forms the foundation of the laws about release of debt and slaves, and the Year of Jubilee which impacted on property rights. But it is also included in the Ten Commandments – the great statement of moral laws that are meant to be eternal, and all of which are repeated in the New Testament. If that’s not enough, is is also a Creation Ordinance, originating at creation itself as God rested on the seventh day (we’ll see more of this later in this series). The context of Leviticus (including the very next verse, which references idol making) is clearly cultic. Maybe this Sabbath law fits in every category of laws. And yet Jesus seems to abolish our observance of a “rest day” when He tells us that we were made for the Sabbath, and not the Sabbath for us (see Mark 2:27). But He and His disciples observed the Sabbath, and the Apostles continued to do so throughout the book of Acts. Colossians 2:16-17 seems to indicate this was a controversy in the early church, and that we should not adhere to it. To make it even more confusing, the early Christians shifted any form of observance of a “Sabbath” to the first day of the week anyway.

I’m not going to try and clear up these centuries old arguments about the Sabbath here. My main point is simply that many laws defy simply categorisation. In theory it sounds great to talk of “moral laws”. In reality it’s just not that clear.

The rest of Leviticus 19 is a complete mix and match of different categories of laws that further illustrate this point:

- Ceremonial or sacrificial – sacrifices (19:5-8)

- Civic or civil – not harvesting to the edge of your field to leave something for the poor (19:9-10 – or is this a moral law?); holding back wages (19:13 – again, maybe this is moral?); standing up for the elderly (19:32 – or is this a moral issue?); treating foreigners well (19:33-34 – or is this moral?); using dishonest weights and measures (19:35-36 – surely this too is moral?)

- Food, health or cleanliness – endangering other people’s lives (19:16 – or is this a moral law?); eating raw meat (19:26 – or is this ceremonial?)

- Moral – Steal, lie, deceive, defrauding others, cursing the deaf or tripping them up (is this just a civic law?), partiality against the poor, perverting justice (is this a civic law?), slander (19:11-16); seeking revenge (19:18); having sex with a female slave (19:20-22); forcing your daughter into prostitution (19:29 – or is this cultic?)

- Cultic – divination and magic (19:26, 31); tattoos (19:28 – this is commonly thought to be cultic, but is it?);

- Finally, “I really have no idea” category (do you?) – Mating different kinds of animals, planting your field with two kinds of seed, and wearing clothing woven of two kinds of materials (19:19 – are these ceremonial or somehow cultic?); cutting your sideburns or edges of your beard (19:27 – is this ceremonial?).

Maybe you did better than me at seeing the “obvious” categories these all fit into. Of course, as we’ve seen above, they’re actually all cultic, given the context of Leviticus 18 and 20. We do not get to decide which laws are intended to be universal and which are not. The fact that some of these laws have universal and eternal relevance does not change the fact that in this context, the only way we can be consistent with them is to treat them all as cultic, with limited application to Israel in ancient history.

If they’re not cultic, it becomes quite difficult to distinguish which are applicable today and which are not in Lev 19: leaving the edges of your fields unharvested, so the poor can collect food (Lev 19:9), not paying daily wages (Lev 19:13), not eating fruit from a newly planted fruit tree for at least four years (Lev 19:23-25) or eating your meat too rare (Lev 19:26). We ignore these commands and treat them as not applicable for our lives today. If we do not apply these laws today, then on what basis can we apply the laws about homosexuality?

Leviticus 20 is a repeat of the laws from Leviticus 18 and 19, with punishments specified, further strengthening our case that this is a discreet unit of laws – which are cultic in nature. The death penalty – by stoning – is required for child sacrifice, cursing of parents, committing adultery, sex with a mother-in-law or a daughter-in-law, men having sex with men and bestiality (even the animal must be killed). If a man marries a woman and her daughter, they are all to be burned in the fire. Having sex while a woman is menstruating is to be punished by cutting both people involved off from the tribe for a period of time (this is specified in Lev. 15). Incest is punished by the people involved being childless (not a bad thing, given our modern understanding of genetics). We’ll look at how we understand these punishments in a moment. For now, we simply note that once again it is very difficult to consistently apply categories to these laws.

For example, here are a few other laws from the book of Leviticus that we might battle categorise:

- Leviticus 21 contains rules for priests. The priest is to marry a virgin only (they cannot marry someone who was a prostitute or previously married). Nobody with physical disabilities may become a priest. Are all these rules applicable today as moral rules, or are they only ceremonial and therefore not in force today?

- Leviticus 25 and Deuteronomy 15 talk about a Sabbath year, a year of cancelling debts, and the Year of Jubilee. There is no reason why the restoration of land rights envisaged in the Jubilee concept, together with redistribution of wealth, freedom from economic debt and release of slaves, are not moral issues and therefore universal and eternal. Yet they are ignored today, and considered sacrificial.

- Leviticus 27 provides the monetary values that can be paid to redeem someone who has been consecrated to God. Women are valued at 60% of the value of men. Is this a universal principle applicable today? Or can we ignore this as a civil law that is culturally connected?

There is only one consistent way to decide which Old Testament Laws and which do not, and that is to only follow laws that are specifically renewed in the New Testament. If we want to try and follow just some laws of the Old Testament, it gets even trickier to explain why we would not follow the punishments prescribed for those who break these laws.

If we apply the Law, we must apply the punishment

Let me start in a possibly unexpected place with this principle. According to Numbers 5:11-31, if a man suspected his wife of having an affair, but had no physical proof, he could take her to the priest who would sweep some dust off the Tabernacle floor, mix it into a vessel of water and make the wife drink it. If the dusty water didn’t make the woman sick and sterile, then she was innocent, but if her belly swelled up with pain, then she was guilty. Seriously, just read this straight from the Bible. I am sure we feel that laws of adultery are universal and eternal moral laws. So, is this strange practice, together with the punishment of sterility, still applicable today? I am sure we’d say that it isn’t.

Similarly, we can look at the death penalty. This was the punishment for homosexual sexual activity commanded in Leviticus 20:13. The death penalty was actually demanded for many different offences, just in the book of Leviticus, including: child sacrifice (Leviticus 20:2); cursing parents (20:9); various sexual acts, primarily incestuous or familial (20:11-15); being a medium or wizard (20:27); blaspheming the name of the Lord (24:17); murder (24:21); also, persons devoted to destruction in holy war must be killed, never ransomed (Lev. 27:29). Other offences punishable by death in Old Testament Law: touching Mt. Sinai while God is giving the law (Exodus 21:12); striking a person mortally (21:15); striking one’s own parent (21:16); kidnapping (21:17); cursing a parent (21:29); failure to restrain a violent animal (22:19); bestiality (31:14); Sabbath breaking (31:15, 35:2; compare with Numbers 15:35); anyone other than a Levite coming near the tabernacle (Numbers 3:10); anyone other than Moses, Aaron, or Aaron’s sons camping in front of the tabernacle to the east (Numbers 3:38); an outsider coming near the altar area (Numbers 18:7); and, striking another with an object so that the other dies (Numbers 35:16-21; see also Deuteronomy 19:11-13); divining by dreams to lead Israel to idolatry (Deut. 13:1-5) and enticement to idol worship, even by a family member (13:6-11); a town that goes astray to worship idols is to be destroyed utterly, including its livestock (13:12-18, see also Deuteronomy 7, Joshua 2, 8, 10, etc.). Children who disobeyed their parents were also to be executed (Deut. 21:18-21). Various ritual offenses by the priests described as incurring guilt and bringing death include: failure to wear the properly designed priestly robes, turban and undergarments into and out of the holy place (Ex. 28:31-43); failure to wash hands and feet before entering the Tabernacle or at the altar (Ex. 30:17-21); failure to stay the full seven days of the priestly consecration rite (Lev. 8:33-35); drinking wine or strong drink when entering the tabernacle (Lev. 10:8-9); failure to make proper ritual cleansing after sexual emissions and discharges of blood (Leviticus 15); failure to prepare properly before entering the tabernacle on the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16); and violations of bodily cleanness regulations by a priest entering the tabernacle (Lev. 22:1-9).

Notice that the laws mentioned above come from every category discussed above except the dietary and health category.

Clearly, Christians quoting Leviticus 20:13 against homosexuals do not support the death penalty for those committing same-sex acts. But why not? If they do support the death penalty for homosexual sex acts, do they support the death penalty for all of the offences listed above? If not, why not?

Probably the best summary of the traditional approach to the Old Testament I’ve ever read is by Tim Keller, and can be found here. He believes that the moral law is universal and still applies, but that we don’t apply the penalties anymore because Israel was a nation state and all penalties then were civil penalties. The church is no longer a nation state, and so we apply church discipline now, not capital punishment. He argues that Paul says that a man caught in adultery was to be put out of the church, and this, rather than public stoning to death, is the new punishment (1 Corinthians 5:1ff. and 2 Corinthians 2:7-11). If this is new way we are to deal with putting people to death, Keller does not explain why we do not apply this new punishment consistently across all the sins mentioned above. Nor does he explain how we decide which laws are moral and therefore universal as discussed above.

Keller concludes:

“Once you grant the main premise of the Bible — about the surpassing significance of Christ and his salvation — then all the various parts of the Bible make sense. Because of Christ, the ceremonial law is repealed. Because of Christ the church is no longer a nation-state imposing civil penalties. It all falls into place. However, if you reject the idea of Christ as Son of God and Savior, then, of course, the Bible is at best a mish-mash containing some inspiration and wisdom, but most of it would have to be rejected as foolish or erroneous.”

Keller’s argument is compelling in the abstract, but falls down when actually applied to the text. I agree with him completely when he concludes that as Christians we cannot follow all the Old Testament laws. I just believe it goes further: we can’t follow any of them. We are people of a New Covenant.

The New Covenant

The Law we’ve been speaking about was given to Moses, deliberately and consciously as a covenant between God and the people of Israel. This is made clear over and over again in the formulation of The Law. The central theme of Christianity, though, is that Jesus Christ has created a new covenant for us. This new covenant was prophesied in the Old Testament – for example, in Jeremiah 31:31-34, “‘The days are coming,’ declares the Lord, ‘when I will make a new covenant with the people of Israel and with the people of Judah. It will not be like the covenant I made with their ancestors … I will put my law in their minds and write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people….”. It is referenced in Romans, Hebrews (see especially 8:8-13), Galatians, Ephesians 2, 1 Corinthians 11:25, 2 Corinthians 3:6, and elsewhere.

The Law was part of the Old Covenant, and has been fulfilled and superseded in Christ.

Galatians 3:23-25 says, “Before the coming of this faith, we were held in custody under the law, locked up until the faith that was to come would be revealed. So the law was our guardian until Christ came that we might be justified by faith. Now that this faith has come, we are no longer under a guardian.” Romans 6-8 are all about how the old law has been replaced by a new one, and that we are no longer under the law. Paul is clear that this does not mean we can do anything we want to do, or that there are no laws at all. But the only laws that apply to us now are the laws that have been given to us as part of the New Covenant. This echoes what Jesus Himself clearly taught on many occasions, often starting with “You have heard it said, but I tell you…”.

Hebrews 8-10 tells us that the laws about sacrifices have been done away with and have been replaced and fulfilled in Christ’s death and resurrection. So, for example, Hebrews 8:13 says, “In that He says, ‘A new covenant,’ He has made the first obsolete. Now what is becoming obsolete and growing old is ready to vanish away.”

One final example comes from Ephesians 2:11-22, in which Paul is saying that The Law actually divided Jews and Gentiles in the past, as the Law was only for the Jews. Now, we are free of the Law, and can be united:

- “Therefore, remember that formerly you who are Gentiles by birth and called ‘uncircumcised’ by those who call themselves ‘the circumcision’ (which is done in the body by human hands) – remember that at that time you were separate from Christ, excluded from citizenship in Israel and foreigners to the covenants of the promise, without hope and without God in the world. But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility, by setting aside in his flesh the law with its commands and regulations. His purpose was to create in himself one new humanity out of the two, thus making peace, and in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility….”.

In place of the Old Testament law, Christians are under the law of Christ (Galatians 6:2), which is to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind…and to love your neighbour as yourself” (Matthew 22:37-39). If we obey these two commands, we will be fulfilling all that Christ requires of us: “All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments” (Matthew 22:40). This does not mean that the Old Testament law is irrelevant today. Many of the commands in the Old Testament law fall into the categories of “loving God” and “loving your neighbour”. The Old Testament law is a good guide for knowing how to love God and knowing what goes into loving your neighbour, and it convicts people of our inability to keep the law, pointing us to our need for Jesus Christ as Saviour (Romans 7:7-9; Galatians 3:24). The Old Testament law does not apply to Christians today. The Old Testament law is a unit (James 2:10) – either all of it applies, or none of it applies. If Christ fulfilled some of it, such as the sacrificial system, He fulfilled all of it.

The Old Testament law was never intended by God to be the universal law for all people for all of time. We are to love God and love our neighbours. If we obey those two commands faithfully, we will be upholding all that God requires of us.

So, anything goes? There are no laws?

By saying that we can’t look to the Old Testament for laws applicable today doesn’t mean that there are no laws for today. We look to the New Testament for these – and it is to the New Testament that we shall shortly turn in this series on homosexuality and the Bible. By saying we can’t look at Leviticus for laws against homosexuality, we don’t open the door to any and all sexual sins. We know from Scripture, and from general morality, that sexual encounters must be consensual, for example. This is all we need to prohibit bestiality and paedophilia. Other principles, such as mutuality, loving others more than ourselves and self-sacrifice all play a part in establishing a set of New Covenant principles that govern relationships and sexual ethics.

We definitely have laws. But not Old Testament ones. If I have convinced you already with my argument, you can probably skip the next section of this series, and jump to the analysis of the New Testament verses. But, even though I believe I have adequately shown why Old Testament laws are not applicable to us today, let’s look next at the Old Testament prohibitions against same-gender sexual activity anyway and see what they actually say. You’ll discover that it’s not what you think. And I’ll make some important points that we’ll need to understand later about idolatry, when we look at Romans 1.

Previous article in this series: Sodomites in Genesis (and Judges)

Next article in this series: Leviticus: The Holiness Code, Ancient Sex Ethics and Abominations

Click here to see the index of the full series of blog posts on the issue of Christians, the Bible and homosexuality.

If you’d like to be alerted when a new post is uploaded, sign up for the Feedburner email alert service.

4 thoughts on “The Bible and Same Sex Relationships, Part 5: Consistency, Punishments and the New Covenant”