Summary

|

We’re at part 7 of this series, and we arrive now at the New Testament. There are three verses that reference same-gender sexual activity directly, and some references by Jesus to the form of marriage (made in response to a question about divorce). Before we deal with each of these verses in turn, we need to understand the prevailing culture of the Graeco-Roman world in which the NT was written. This context is vital to our own understanding of the Biblical texts we will look at.

Some people use this cultural context to say that Paul’s commands to us today can safely be ignored. They put these in the same category as the length of men’s hair, women wearing jewellery or the repeated commands to greet each with “a holy kiss”. While it is important to understand how Biblical instructions and principles should be applied today – and we will see when we look at Romans 1 in a few posts from now that we cannot avoid the question of applicability in one key area of Paul’s “argument against nature” – I don’t rely on this line of argument to make my point. I don’t think Paul was anti-women, and I don’t think Paul was anti-gay. I think we’ve misunderstood his instructions, and in some cases even mistranslated his words.

So, to understand Paul – and Jesus – better, we need to get an understanding of how the world they lived in treated homosexuality and homosexuals – and dispel some myths in this regard. This will help us understand what they were saying when they talked about it.

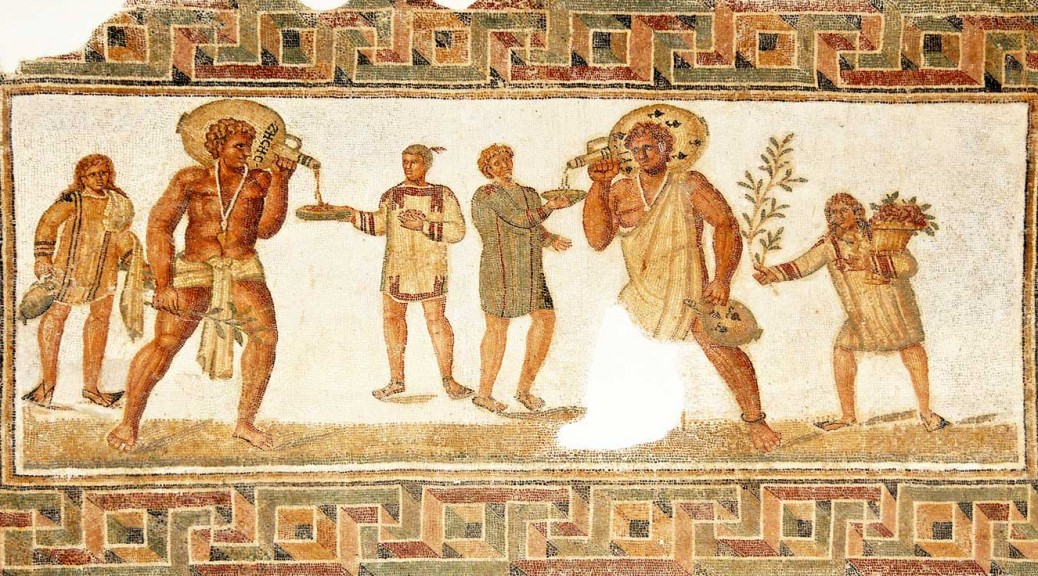

The Graeco-Roman world

A few years before Jesus was born, in 27BC, Octavian became sole ruler of Rome, ended the Roman Republic and began the Roman Empire. He became Augustus Caesar, and ruled until 14AD, rapidly expanding the Roman Empire. Judaea and the Middle East were conquered in 6BC, becoming Roman provinces. In 54AD, Nero became Emperor, and he waged a brutal assault on both Jews and Christians, culminating in the destruction of the temple of Jerusalem in 70AD.

Throughout Jesus’ lifetime and the period of the writing of the New Testament (commonly held to have been completed towards the end of the first century AD), the Roman Empire, with it’s amalgam of Greek traditions and language with Roman culture and law, was the dominant cultural backdrop. The most significant issue for the early followers of Christ, who were all Jewish, was how to take the message of Jesus – a Judaean-based Jew – and make it relevant and accessible to “the Gentiles”. Paul, a Jewish scholar, trained in Greek and a religious leader held in high esteem yet also a Roman citizen, was the ideal “Apostle to the Gentiles”. Many of his writings address this specific issue, with the books of Romans, Galatians and Hebrews (who’s author is unattributed) almost entirely devoted to this topic.

Jewish culture had always been defined by the notion of “being separate” or being different from the surrounding nations, as we saw in the previous section of this series. But the new Gentile Christians had no such heritage. As Christianity spread into the Greek and Roman cities, the early church leaders had to spend many hours debating in what ways Christians could continue their lives and retain their culture, and in what ways they had to be different and separate from the world in which they lived. They also had to decide which of the Jewish customs and laws were required to continue into Christian tradition, and which could be abandoned. This was not always easy, and arguments between Peter and Paul are actually recorded (see, for example, Galatians 2:11-14). Letters to Thessalonica, Ephesus (and to Timothy, their leader), Corinth, Philippi and Rome all deal with these issues in detail.

In the context of our study on whether we can affirm same sex marriage and whether same-gender sexual activity is sinful or not, we therefore need to understand the Greek and Roman world’s attitudes to homosexuality, so we can understand what the Apostles and Jesus were saying to the people at that time.

The Graeco-Roman view of sex

The sexual ethics generally accepted in the Greek and Roman world were very different from those we generally hold to today. Women were considered to be inferior to men, and wives were considered the property of their husbands. Women ran the home and managed the slaves, while men did the work. Upper born men would engage in public life and government, while lower born men would do physical labour, but the rules were the same: men and women lived separate lives. Sexual enjoyment was largely for adult men, who indulged their desires with male and female lovers quite openly. Robin Scroggs, in “The New Testament and Homosexuality” says: “Public culture of these centuries was male oriented, and the apposite intellectual and, indeed, effective partner to a male was another male.”

Male-male love was actually extolled as the highest form of love by many philosophers, and was not seen as simply fulfilling physical desires. For example, Plato wrote: “[Homosexuality] is regarded as shameful by the Ionians and many others under foreign domination. It is shameful to barbarians because of their despotic government, just as philosophy and athletics are, since it is apparently not in the best interests of such rulers to have great ideas engendered in their subjects, or powerful friendships or physical unions, all of which love is particularly apt to produce. … Wherever, therefore, it has been established that it is shameful to be involved in homosexual relationships, this is due to evil on the part of the legislators, to despotism on the part of the rulers, and to cowardice on the part of the governed.” [Symposium 182B-D]

Consider this passage from Plutarch’s Er?tikus, where Protogone’s says:

- “Genuine love has no connexion whatsoever with the women’s quarters. I deny that it is love that you have felt for women and for girls, anymore than flies feel love for milk or bees for honey. … But that other lax and housebound love, that spends its time in the bosoms and beds of women, ever pursuing a soft life, innovated amid pleasure devoid of manliness and friendship and inspiration – it should be proscribed.” (750C)

The primary form that this male-male sexual satisfaction took was pederasty (literally, “the love of boys”). This was invariably a voluntary relationship between an adult male and a young boy. The adult male assumed the active sexual role, while the younger was passive. Pederasty was not hidden, but openly practised, almost universally condoned, in some quarters extolled and seen by many as an ideal in the normal course of growing up. Many of the adults engaged in pederasty would have been married. Many of the youths involved submitted to this relationship as a means of being educated or of developing military prowess and skills. As these young boys grew up, they would often swap their passive role for a more adult active role, seeking their own passive partner.

Key to understanding this is that the focus point of physical beauty in both Greek and Roman worlds was the male body, and specifically the youthful male body in androgynous form. There are hundreds of references available to classical literature that extol the beauty of young men, and make this the focal point of eroticism in society. When the young man began to show more adult features, such as growing hair or becoming more muscular, he began to lose his sexual appeal.

Robin Scroggs, in “The New Testament and Homosexuality“, says:

- “In some quarters pederastic relations were extolled, in almost all quarters condoned. There was no need to be ‘in the closet’ about homosexual preferences. Thus it is important to keep in mind that Graeco-Roman pederasty was practiced by a large number of people in part because it was socially acceptable, while by many people actually idealized as a normal course in the process of maturation.”

Homosexuality in Greek and Roman culture was openly accepted in a variety of forms:

- Same sex marriages were legal, commonplace and accepted as normal. This was for both men and women.

- Roman men were free to enjoy sex with other males without a perceived loss of masculinity or social status, as long as they took the dominant or penetrative role.

- Prostitution was considered a normal part of life, with both male and female prostitutes available to free born adult men. Married men were the clients of these prostitutes. In Rome, prostitution was not just legal, it was actually taxed and the revenue from prostitutes constituted a significant part of public income. Male prostitutes even had their own legal public holiday.

- Many Roman citizens kept slaves for the sole purpose of sexual activity. These were both male and female, with homosexual sex being preferred. Many of these slaves were acquired through kidnapping.

- Throughout the Roman Empire, there were brothel houses filled with young boys enslaved as sex objects. It was not uncommon to castrate these boys in order to prolong their youthful appearance, and therefore their usefulness as sex slaves.

- Young boys would make themselves voluntarily available as sexual partners to older men for a variety of reasons, including the guarantee of safety, education, social advancement, gifts and even adoption. There are many accounts of significant leaders doing this. For example, Mark Antony was a male prostitute as a young man. These young men were expected (most of the time) to be completely passive recipients during the sexual encounters. If they did experience sexual satisfaction, they would be derided as no better than prostitutes.

- There are two categories of pederasty which were not considered acceptable, however. The firsty was freeborn Roman citizens voluntarily becoming ‘call boys’. The literature does not use this term, referring to them simply as prostitutes, but over and over again a distinction is made between higher and lower forms of pederasty. For example, Aeschines in Timarchus (137) says, “To be in love with those who are beautiful and chaste is the experience of a kind-hearted and generous soul; but to hire for money and to indulge in licentiousness is the act of a man who is wanton and ill-bred.”

- The second category of pederasty not acceptable was coerced sexual encounters, or rape.

Having said that “homosexuality” was openly accepted, it is important to note that actually the Greeks and Romans really did not have the category of “homosexual” as we would have it today. Homosexuality was so part of culture, that neither Greek nor Latin even had specific words for these sexual orientations (although there were many different words for various same-gender sex acts). As John Boswell states in “Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality“:

- “In the ancient world so few people cared to categorize their contemporaries on the basis of the gender to which they were erotically attracted that no dichotomy to express this distinction was in common use. People were thought of as ‘chaste’ or ‘unchaste,’ ‘romantic’ or ‘unromantic,’ ‘married’ or ‘single,’ even ‘active’ or ‘passive,’ but no one thought it useful or important to distinguish on the basis of genders alone, and the categories ‘homosexual’ and ‘heterosexual’ simply did not intrude on the consciousness of most Greeks [or] Romans.”

Opposition to Pederasty

In the vast Roman Empire each of the city-states and provinces had autonomy and diverse cultures. The “classic literature” also spans a period of over 800 years, with evolving cultural mores. We can therefore find opposition to the sexual ethic outlined above. Different attitudes prevailed in different places.

Famously, by the time of Nero, the Imperial capital in Rome was characterised by moral decadence. However, it is incorrect, as Boswell points out, to characterise everyone by what we know of Nero’s courts:

- “The common impression that Roman society was characterized by loveless hedonism, moral anarchy, and utter lack of restraint is as false as most sweeping derogations of whole peoples; it is the result of extrapolations from literature dealing with sensational rather than typical behavior, which was calculated to shock or titillate Romans themselves. Most citizens of Roman cities appear to have been as sensitive to issues and feelings of love, fidelity, and familial devotion as people before or after them, and Roman society as a whole entertained a complex set of moral and civil strictures regarding sexuality and its use. But Roman society was strikingly different from the nations which eventually grew out of it in that none of its laws, strictures, or taboos regulating love or sexuality was intended to penalize gay people or their sexuality; and intolerance on this issue was rare to the point of insignificance in its great urban centers. Gay people were in a strict sense a minority, but neither they nor their contemporaries regarded their inclinations as harmful, bizarre, immoral, or threatening, and they were fully integrated into Roman life and culture at every level.” In “Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality“.

Critics of these sexual practices – which included the Jews – decried particular practices, including forced sex slavery, kidnapping of young boys and girls for sex, and the role reversals of free born Roman men becoming the passive partners in sexual activities. The reasons for being critical include the fact that these young boys were effeminate and unmanly, were greedy and (in the case of the effeminate call-boys) had multiple lovers, thus provoking jealousy. There were also concerns about abuse and the impact of these relationships on the boys. It’s important to note that the objections in the classical literature never reference the same-gender nature of the relationships as the reason for the objection.

The Graeco-Roman world that forms the backdrop to the writing of the New Testament had a very specific dominant sexual ethic. Where the Bible gives instructions on sexuality, we need to understand these in relation to this cultural milieu. Is the Bible affirming what is happening, or running counter-culturally to it? Is it being more conservative than the culture, or is it being progressive? These questions help us understand how to interpret a variety of issues, from eating meat sacrificed to idols and wearing makeup to the role of women in the church and Christian attitudes to slavery.

We will next turn our attention to Paul’s criticism of homosexuality, and his instructions to the churches at Corinth and Ephesus on “male bedders” and “soft” men.

Previous article in this series: Leviticus: The Holiness Code, Ancient Sex Ethics and Abominations

Next article in this series: Male-Bedders – the meaning of ‘arsenokoitai‘

Click here to see the index of the full series of blog posts on the issue of Christians, the Bible and homosexuality.

If you’d like to be alerted when a new post is uploaded, sign up for the Feedburner email alert service.

7 thoughts on “The Bible and Same Sex Relationships, Part 7: Graeco-Roman culture and homosexuality”